Russian VA-111 Shkval — Supercavitation Torpedo Explained

Shkval: Cold War Sprint Torpedo

Russia’s undersea weapons history includes a few designs that look reckless on paper. The VA-111 Shkval supercavitation torpedo sits near the top of that list. It traded stealth and finesse for raw closing speed, and it did so decades before today’s unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) became mainstream.

Even now, that trade-off feels relevant again. Navies worry about short-range, high-tempo fights around choke points, ports, and carrier screens. Meanwhile, UUVs and naval drones keep expanding the undersea “sensor and shooter” web. In that environment, a sprint weapon can still influence tactics, even if it remains niche.

What Shkval Is

At its core, Shkval is a supercavitating torpedo designed to run at extreme speed once it reaches cavitation conditions. Open sources widely describe it as exceeding 200 knots (about 370 km/h, roughly 230 mph) underwater. Shkval also fits standard 533 mm torpedo tubes for submarines, which matters. It means the weapon concept plugs into common Soviet/Russian launch infrastructure rather than requiring peculiar platforms.

Supercavitation Basics

Supercavitation sounds like science fiction; however, the physics are straightforward. Water drag rises sharply with speed. Therefore, Shkval reduces drag by surrounding itself with a gas cavity, so the body touches far less water. In effect, the weapon “rides” inside a bubble. That bubble reduces friction dramatically, which enables speeds conventional torpedoes cannot match.

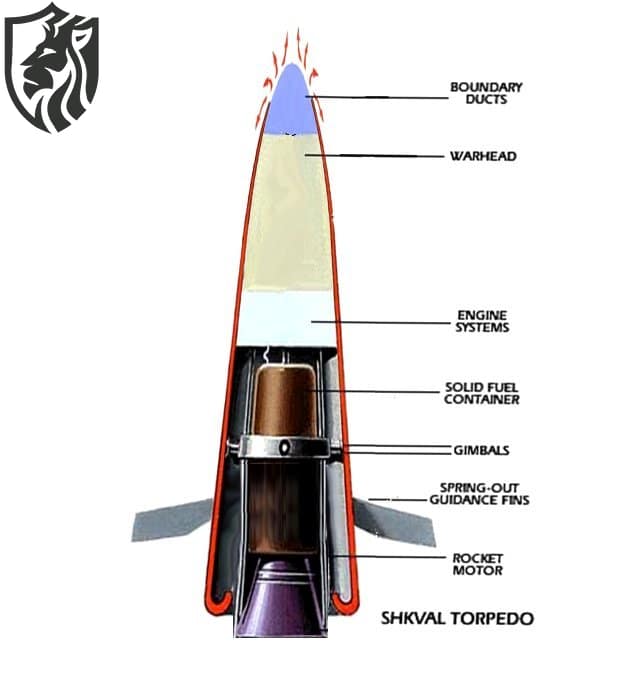

Hardware That Makes the Bubble

Shkval’s design uses a nose device (often described as a cavitator) to start and stabilize the cavity. Moreover, designs discussed in open literature describe gas management to sustain that cavity as speed increases. This is also why guidance is challenging. The bubble isolates much of the body from the surrounding water, so classic fin control becomes less effective. As a result, “turning hard” and “homing precisely” become engineering nightmares.

How Shkval Reaches Sprint Speed

Most accounts describe a two-step problem: first reach supercavitation speed, then sustain it. Shkval reportedly accelerates quickly after launch, then uses rocket-style propulsion to keep velocity high. That concept explains both the appeal and the penalty. The torpedo arrives fast, yet it also creates a loud, turbulent signature. In other words, the weapon announces itself.

Development Timeline and Lessons

Shkval’s origins sit in the Cold War push for asymmetric answers to NATO undersea power. Public sources place the program’s design era in the 1960s–1970s, with operational fielding often cited as 1977. Your draft also highlights early trials and setbacks before a later breakthrough. That pattern fits the general story of supercavitation: it is brutally difficult to achieve stable, repeatable performance at scale.

Performance: Speed, Range, and payload

The headline remains “speed: 200+ knots” in multiple public references. Range is more constrained. Open sources commonly cite a short combat reach, often in the 7–13 km band depending on variant and source. Shkval is also described as capable of carrying either a conventional or nuclear payload. That detail matters because it hints at the original doctrine: a nuclear option reduces the need for pinpoint terminal accuracy.

Limitations That Matter

Speed does not solve everything. The VA-111 Shkval supercavitation torpedo carries several operational expenses:

- The VA-111 Shkval supercavitation torpedo has a shorter effective range compared to many modern heavyweight torpedoes, which often operate well beyond the Shkval band.

- The vehicle’s maneuverability is limited due to the inherent difficulty of controlling it inside a cavity.

- The high detectability is attributed to the intense noise and disturbance generated by the cavity and propulsion.

Therefore, Shkval fits “high-risk, high-speed” use cases more than day-to-day submarine stalking.

Why Shkval Matters in the UUV Era

So why discuss it now? This is due to the evolving nature of undersea warfare. First, UUVs can extend detection and classification forward of crewed submarines. Consequently, a submarine (or unmanned launcher) might obtain a cleaner cue for a short-range, time-critical shot. Second, navies increasingly plan for dense littoral environments, where engagement windows shrink and reaction time matters.

That is why some analysts keep revisiting the sprint-torpedo idea, even while acknowledging the drawbacks. If you want a related internal read on hard-kill defense concepts, your coverage of Germany’s interceptor-style anti-torpedo thinking offers useful context. DEFENSE NEWS TODAY Another broader internal starting point is your main hub for naval and undersea content.

Realistic Modern Upgrades

A revived Shkval concept would need upgrades that match its weaknesses:

- Improved guidance logic for straight-run intercept geometry is necessary, as tight terminal homing within a cavity remains challenging.

- Enhancing the range and energy management is crucial, as shots within the range of 7–13 km are limited.

- Reducing the signature is challenging, although it is the most difficult aspect to resolve. A supercavitating torpedo body will always create disturbances.

In short, modern electronics can help with planning and control. However, the core physics still impose constraints.

Bottom line

The VA-111 Shkval supercavitation torpedo remains a genuine engineering milestone. It proved that “underwater sprint” weapons could work at operational scale. Yet it also proved the cost of that approach: range, control, and stealth all suffer. Even so, as UUVs expand sensing and targeting options, the sprint-torpedo concept could reappear in specialized roles—particularly where seconds matter more than silence.

References

- https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/14/6247

- https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/russia/shkval.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VA-111_Shkval

- https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2019/october/red-subs-rising

I was suggested this web site by my cousin. I’m not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else

know such detailed about my problem. You are amazing!

Thanks!