Africa Transnational Crime Hub — Security Fallout

Africa is no longer a side route in global illicit trade. Instead, the continent increasingly functions as an Africa transnational crime hub—serving as a source, transit corridor, and end-market at the same time. Researchers at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) argue that, between 2019 and 2025, Africa became deeply embedded in the global criminal economy, with overlapping markets reinforcing each other.

For defense and security audiences, that matters because criminal networks don’t just move contraband. They also shape conflict dynamics, bankroll armed groups, and corrode state capacity. Moreover, they exploit the same seams militaries worry about: ports, borderlands, and governance gaps. To keep this analysis transparent, see How We Verify and related coverage in Defense News Today’s Africa region.

What changed after 2019

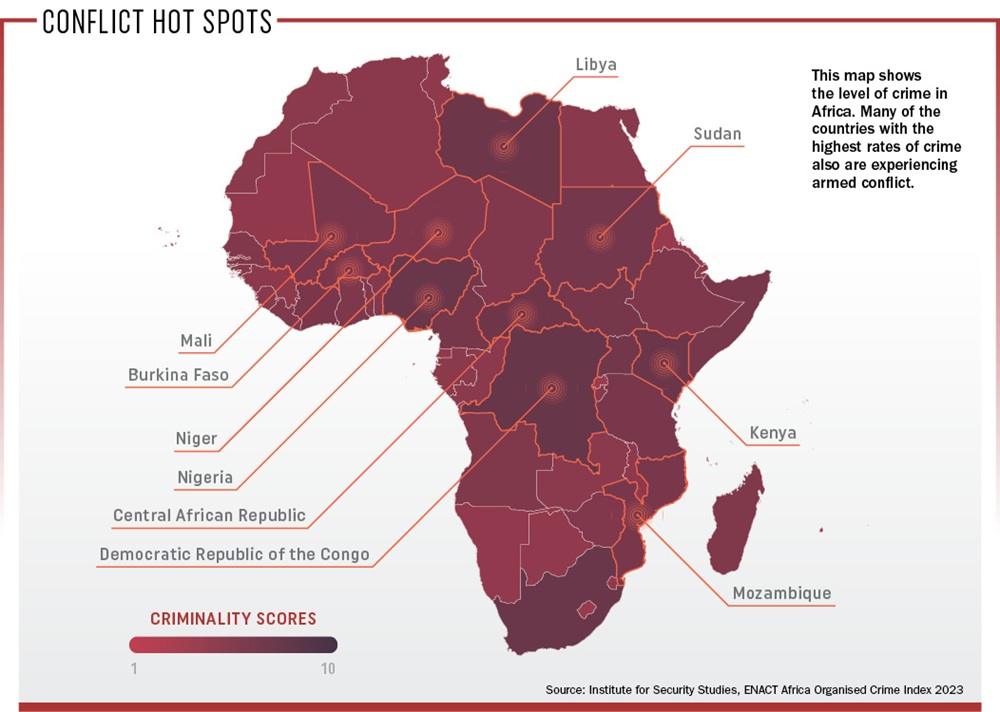

Several structural drivers explain why the Africa transnational crime hub label now fits more often than it did a decade ago. First, many borders remain porous, while enforcement budgets stay thin. Second, corruption lowers the cost of moving illicit goods, because criminals can buy access rather than fight for it. Third, chronic instability creates “ungoverned logistics,” where the state’s writ weakens and armed actors fill the vacuum. GI-TOC’s 2025 Index also points to a steady growth in criminal markets and criminal actors since 2019. In parallel, resilience often lags behind criminality—meaning states struggle to keep pace even when they improve seizures or coordination.

Drug routes: Atlantic & Indian Ocean

Drug trafficking sits at the center of the Africa transnational crime hub story because geography works in traffickers’ favor. Africa lies between cocaine production in South America and high-value demand in Europe. At the same time, it sits along routes linking heroin and synthetic drug production in southwestern Asia to markets elsewhere.

Ports to Sahel: West Africa cocaine flow

West African ports have become attractive nodes for cocaine concealment in shipping containers, fishing craft, and yachts. From there, traffickers push loads across the Sahel to North Africa, then onward into Europe—or into emerging African consumer markets. GI-TOC-linked reporting notes major seizures in 2024: Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, and Senegal reportedly intercepted nearly 4.5 metric tons of cocaine, while Morocco intercepted another 1.5 metric tons the same year. However, interdictions can mislead analysts. Seizures may reflect better policing and cooperation rather than a true fall in flows. In other words, an impressive “tonnage headline” can still sit atop a much larger hidden pipeline.

Why the Southern Route is rising

East Africa has also become pivotal for heroin and synthetic drugs, particularly as interdiction pressure increased along more traditional Balkan pathways. Traffickers have leaned on Indian Ocean access points in Kenya, Mozambique, South Africa, and Tanzania, using maritime entry and then redistributing inland. For militaries and coast guards, this shifts emphasis toward maritime domain awareness, port screening discipline, and intelligence fusion—because the first decisive interception opportunity often appears at the coastline, not deep in the interior.

Wildlife, rosewood and smuggled gold

Resource crime ranks among Africa’s most pervasive illicit markets in 2025, behind financial crimes and human trafficking in GI-TOC’s framing. That matters because resource trafficking can look “non-military” on paper, yet it funds violence and weakens governance in practice. Between 2015 and 2021, African states reportedly accounted for 19% of global illegal wildlife trafficking, with elephants, pangolins, rhinoceroses, crocodiles, and parrots among key targets. The demand pull often sits in Asian markets, which shapes routes, concealment methods, and laundering techniques. The illicit plant trade also poses a significant threat.

GI-TOC-linked reporting says the illegal trade in plants—especially rosewood shipped to China—costs African nations a collective $17 billion per year while damaging ecosystems and communities. Meanwhile, gold smuggling moves tens of billions of dollars out of African economies annually, stripping tax revenue that could fund security-sector reform and public services. Critically, gold revenue can also underpin active conflicts, including Sudan’s civil war, by financing armed actors and war economies.

Arms trafficking: small arms and coups

Weapon flows complete the Africa transnational crime hub triangle because instability creates demand, and interest sustains trafficking. West African coups and chronic volatility in the Horn continue to energize illicit arms markets, especially small arms. GI-TOC reporting highlights East Africa as a leading theater for weapons trafficking, with high-profile conflicts in places like Somalia and Sudan adding fuel.

The United Nations has estimated up to 40 million illegal weapons may circulate across African states. Analysts also estimate 3 to 5 million of those illegal weapons are likely in civilian hands in Sudan, which amplifies the lethality and duration of violence. One notable “non-event” still matters operationally: the lifting of the international arms embargo on Somalia did not trigger the feared immediate arms race, according to GI-TOC’s reporting. That doesn’t mean risk vanished. It means the shock did not materialize on the expected timeline.

Operational implications

The Africa transnational crime hub problem isn’t only a policing issue. It is a security architecture issue.

- Ports and chokepoints now function like strategic terrain. Container screening, port governance, and anti-corruption controls can have “fleet-level” effects on trafficking volume.

- Borderlands behave like operational depth for criminal networks. Sahel routes, desert crossings, and lake/river systems enable dispersion and redundancy.

- Crime and conflict reinforce each other. Criminal income sustains armed groups; conflict conditions protect criminals. GI-TOC explicitly warns that conflict erodes state control, creating fertile ground for illicit markets that then further undermine governance.

- ISR, not just raids, becomes decisive. Persistent surveillance, financial intelligence, and targeting facilitators can outperform headline-grabbing seizures.

- International cooperation is a force multiplier. Better coordination can raise seizure numbers, yet the goal should be network disruption, not optics.

Bottom line

Africa’s emergence as a transnational crime hub is a result of the convergence of geography, governance gaps, and conflict economics on a large scale. Drug routes exploit Atlantic and Indian Ocean access. Resource trafficking monetizes biodiversity and minerals. Weapon flows feed insecurity and prolong wars. Therefore, an effective response requires more than arrests—it needs durable state resilience, credible border and port control, and sustained intelligence cooperation.

References

- https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/africa-organised-crime-index-2025/

- https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Africa-Index-2025-WEBv2.pdf

- https://adf-magazine.com/2026/01/africa-now-a-global-hub-for-transnational-crime/

- https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/cocaine/Global_cocaine_report_2023.pdf