20 kN Dual-Regen Cooling Aerospike Engine

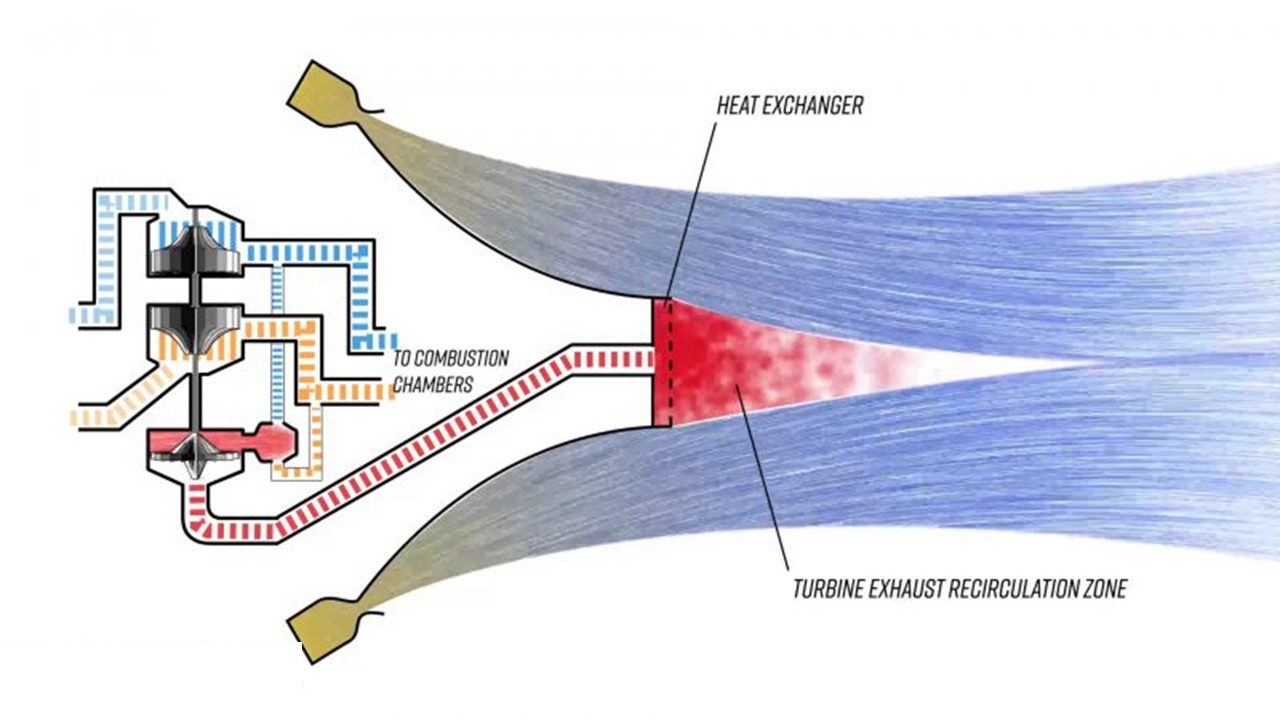

Aerospike engines keep returning to serious conversations for one reason: they promise stronger nozzle efficiency across a wide altitude range. A conventional bell nozzle must “choose” an expansion ratio. Therefore, it performs best in one slice of the climb. An aerospike, by contrast, lets ambient pressure shape the exhaust plume as the vehicle ascends, acting like a virtual nozzle wall. In practice, that can translate into better overall ascent performance—if engineers can keep the hardware alive.

That “if” has always been thermal. Aerospikes expose a lot of surface area to extreme heat. Moreover, the plug or spike sits in the nastiest flow region. Therefore, cooling becomes a crucial aspect, not merely a minor detail. This is where modern demonstrators are interesting: they do not just revisit aerospikes; they attack the heat problem directly with manufacturing and plumbing that older programs could not field economically.

Aerospike Basics

An aerospike (often described as a plug nozzle) routes hot gas along the outside of a centerbody. At low altitude, atmospheric pressure squeezes the plume tighter against the spike. However, as pressure drops with height, the exhaust expands farther out, effectively increasing the expansion ratio during ascent. That altitude compensation is the core advantage.

From a defense and security perspective, this feature is important because efficient margins create real options. They can buy extra payload, extra maneuver margin, or extra fuel for range. In addition, higher efficiency can reduce vehicle size for a given mission, which can simplify logistics and basing. None of that is guaranteed, of course. Yet the nozzle concept offers a lever that bell nozzles cannot pull without compromise.

“20 kN” marks a meaningful test scale.

A 20 kN-class engine sits in a useful middle ground. It is large enough to reveal real combustion and cooling behavior. However, it is still small enough to iterate rapidly and test often. That makes it ideal for proving whether a complex nozzle and cooling concept can survive repeated hot-fires without ugly wear patterns. One high-profile example is the DemoP1 demonstrator, described as a 20 kN LOX/LNG aerospike with dual regenerative cooling and additive manufacturing central to the build. Reports also frame it as a key milestone because it pairs a challenging aerospike geometry with modern production methods, rather than treating the design as a one-off laboratory artifact.

Double-Regenerative Cooling Explained

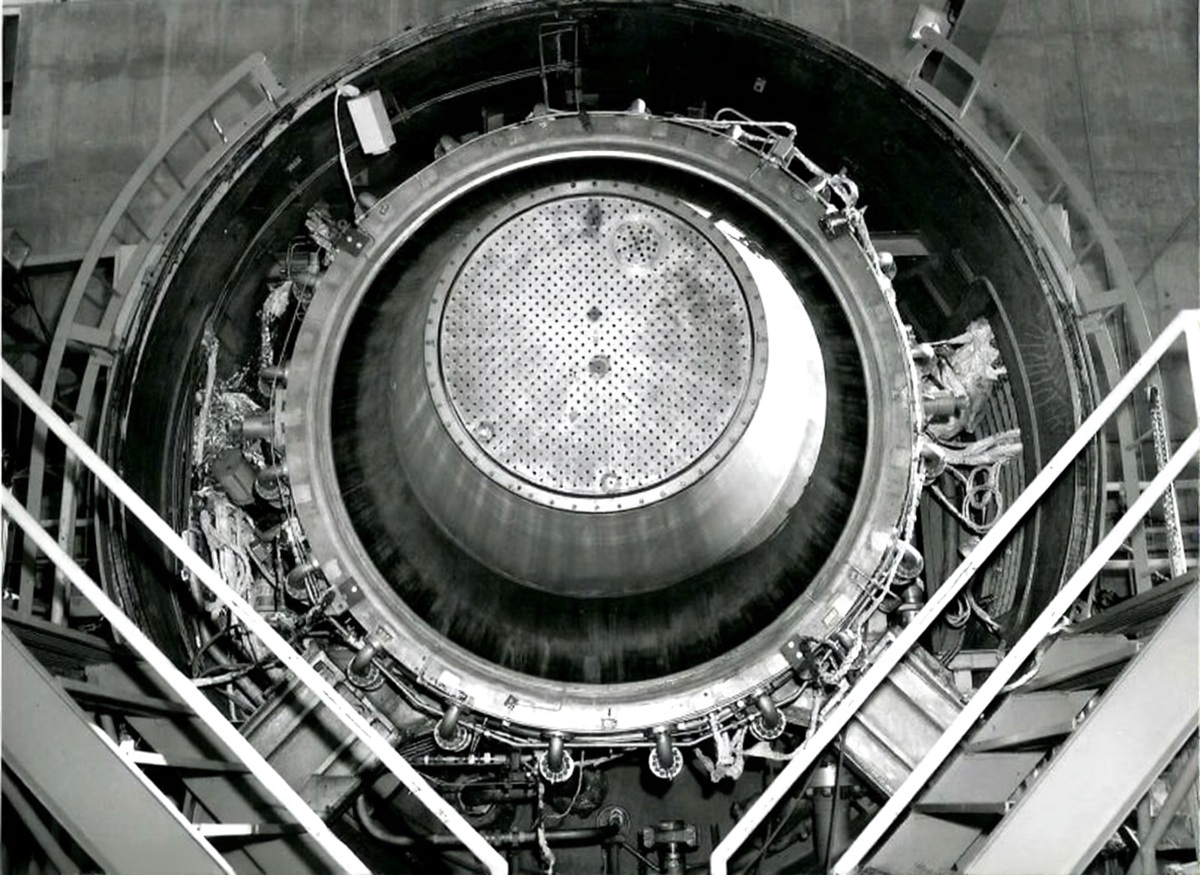

Regenerative cooling is the standard rocket trick: run cryogenic propellant through channels in the engine walls before injection. The propellant absorbs heat, while the metal avoids melting. Meanwhile, the propellant exits the channels warmer and easier to manage at the injector. NASA’s propulsion literature describes regenerative cooling as a core technique in liquid rocket chambers and nozzles, often paired with other approaches like film cooling to manage peak heat flux.

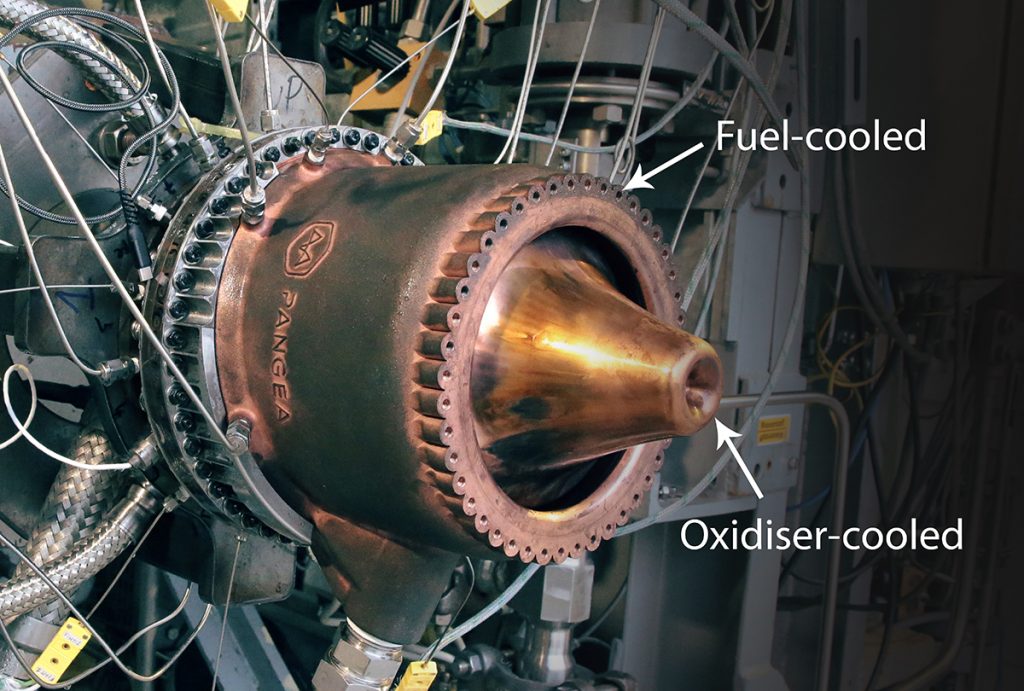

A double regenerative (dual-circuit) approach splits that cooling load into two separate loops. This matters in an aerospike because you do not have just one “wall.” You have the plug/spike surfaces and the outer structure, each with different heat maps and stress profiles. Therefore, two circuits let designers allocate coolant where the heat flux peaks, instead of over-cooling one region while risking hot spots in another.

In the DemoP1-style configuration, published descriptions indicate oxygen cools the internal plug circuit, and methane/LNG cools the external structure. That split is not cosmetic. It reflects a pragmatic decision: the spike sits in the most punishing flow, so it needs a dedicated cooling budget.

Where It Fits

A 20 kN Dual-Regen Cooling Aerospike Engine suits missions that demand efficiency across changing altitudes. For example, small launchers can use it on upper stages to squeeze more delta-v from compact tanks. Moreover, clustered 20 kN units can power responsive micro-launch vehicles, where modularity simplifies production and spares. In addition, defense-relevant space tugs could use it for multi-burn orbital maneuvers that support ISR replenishment and rapid payload repositioning. Finally, hypersonic testbeds may adapt the cooling lessons and plug-nozzle flow control for high-heat propulsion demonstrators, where thermal durability decides program tempo.

The spike drives the entire design.

Aerospike exhaust temperatures can be extreme. An aerospike-related test report depicts exhaust surrounding the spike at approximately 3,500°C, highlighting the importance of cooling in engineering. Once you accept that thermal reality, the architecture follows. You need channels that track local heat flux. You need predictable flow distribution. And you need materials that can move heat out fast without cracking. Otherwise, your “efficient nozzle” becomes a short-lived heater.

Additive Manufacturing Enables it.

Aerospikes reward complex internal geometry. They punish simplistic plumbing. Traditional fabrication can build cooling channels, but it becomes slow and expensive as shapes become more intricate. Additive manufacturing changes that. It can integrate channel networks that follow curved surfaces and vary in cross-section where heat flux changes. Moreover, it can reduce the part count, which often reduces leak paths and assembly risk.

This advantage is why the LOX/LNG dual-regenerative demonstrator matters beyond its thrust class. It is not just “an aerospike.” It is a manufacturing and thermal-management argument: if you can print and qualify the hot section reliably, aerospikes stop being alluring and start being producible.

There’s a performance upside, but it comes with trade-offs.

Aerospikes can improve overall ascent efficiency because they compensate for altitude. However, they do not give you free performance. You still pay in:

- Cooling complexity, because more hot surface area demands more careful design.

- Structural mass, because a larger wall area usually means more material and more plumbing.

- Integration and base heating present challenges, particularly when the spike is truncated to reduce weight and length.

Therefore, the real question is not, “does the nozzle concept work?” It does. The real question is: “can you run it repeatedly, inspect it easily, and build it at a cost that makes sense?” That is the same question every reusable propulsion program must answer.

Why is it relevant for defense?

Aerospike work often appears framed as “space nerd” material. Yet the defense’s relevance is not theoretical. First, efficient propulsion supports responsive launch, ISR satellite replenishment, and resilient space architectures. Second, the same thermal and materials advances can feed into high-temperature structures and cooling approaches used in hypersonic research vehicles. That overlap is why firms like POLARIS talk about aerospikes in the context of reusable spaceplane development. Moreover, aerospikes have a long history of testing and renewed interest, including NASA-led work that gathered flight data for aerospike nozzles. That matters because data, not slides, moves risk down.

2026 Watchpoints: Proof That Matters

If you want to judge whether a Double Regen Cooling 20 kN Aerospike Engine is heading towards operational relevance, watch for four concrete signals:

- The engine should demonstrate repeatable hot-fire campaigns with consistent performance and no progressive hot-spot damage.

- The results of post-test inspections, particularly the initiation of cracks near channel corners and manifolds, are crucial indicators.

- Throttle and start transient stability, because aerospikes can behave differently during ramp-up and shutdown.

- Manufacturing yield, meaning how many printed hot sections pass NDT and pressure checks without rework.

Meanwhile, teams can show steady progress in those areas, and aerospikes gain credibility fast. If they cannot, the concept returns to the drawer—again.

Aerospike Rocket Engine vs Conventional bell-nozzle rocket engine

| Spec / Parameter | Aerospike nozzle rocket engine | Conventional bell-nozzle rocket engine |

|---|---|---|

| Nozzle geometry | Plug/centerbody (annular) or linear ramp | Bell-shaped nozzle |

| Altitude compensation | Yes (plume adapts with ambient pressure) | No (fixed expansion ratio) |

| Common propellants (examples) | LOX/CH₄ (methalox), LOX/LNG, LOX/RP-1, LOX/LH₂, NTO/MMH (less common for modern aerospike demos) | LOX/RP-1, LOX/CH₄, LOX/LH₂, NTO/MMH, N₂O₄/UDMH, HTP/kerosene (varies by programme) |

| Propellant choice impact | Cooling and materials can drive choices; dual-circuit regen often pairs well with LOX + methane/LNG because both can be used as coolants | Very flexible; many mature designs across all major propellant families |

| Best efficiency region | Strong across a wide altitude range | Strong in a narrow design altitude band |

| Sea-level behaviour | Often avoids severe over-expansion issues | Over-expansion/flow separation can occur if vacuum-optimised |

| Vacuum performance | Often comparable to a good vacuum bell, not automatically higher | Excellent when vacuum-optimised |

| Hot surface area exposed | Higher (spike + outer flow surfaces) | Lower for similar thrust |

| Cooling demand | Harder (spike hot spots; complex heat map) | Simpler (more uniform nozzle wall cooling) |

| Typical cooling approach | Aggressive regen; sometimes dual-circuit regen + film cooling | Regen + film cooling common; fewer circuits needed |

| Manufacturing complexity | High; complex channels/geometry (AM helps a lot) | Lower; highly mature tooling and QA |

| Mass & packaging | Can be heavier/complex, but can be package differently | Often lighter and simpler for equivalent thrust |

| Thrust vector control | Can be trickier (methods vary by design) | Usually straightforward (gimbal) |

| Base heating/plume interaction | This process can be more challenging, particularly when truncation occurs. | While aerospikes are more predictable, they still require effective management of base heating. |

Conclusion

Aerospikes never failed on paper. They struggled in metal. Today, dual-circuit regenerative cooling and advanced manufacturing finally give designers the tools to handle the heat, especially at the 20 kN demonstrator scale. A Double Regen Cooling 20kN Aerospike Engine is best considered a stress test of modern thermal engineering: can you cool the spike, keep channel flow stable, and manufacture the hot section reliably? If the answer becomes “yes,” aerospikes move from curiosity to capability.

References

- https://www.metal-am.com/articles/making-the-unmakeablehow-3d-printing-is-bringing-the-aerospike-rocket-engine-to-life/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359431125017764

- https://polaris-raumflugzeuge.de/Technology/Aerospike-Engines

- https://www.nasa.gov/news-release/nasa-dryden-flight-research-center-news-room-news-releases-aerospike-engine-flight-test-successful/